Dec 15 2014 Getting the facts straight at Rocky Flats

We, the collective we, all 6,000 people that were engaged, basically took something that was a significant potential risk to the Denver Metro area and a huge environmental liability, and… did something nobody in the world thought we would be able to do. — Nancy Tuor, former CEO Kaiser-Hill Co.

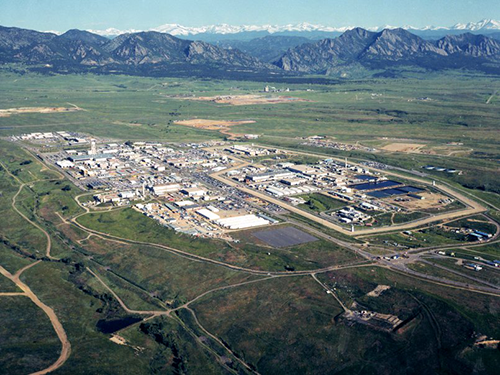

The Rocky Flats Plant in Golden, Colorado produced every plutonium trigger for U.S.-made nuclear warheads since the 1950s. But a 1989 raid by the FBI put a stop to the site’s nuclear production, its operators later pleading guilty to criminal violations of environmental law. Five years later, Rocky Flats sat unused and badly contaminated. The Department of Energy (DOE) called the site “one of the country’s most significant nuclear vulnerabilities,” projecting that cleanup would take 70 years and cost $36 billion.

The Rocky Flats Plant in Golden, Colorado produced every plutonium trigger for U.S.-made nuclear warheads since the 1950s. But a 1989 raid by the FBI put a stop to the site’s nuclear production, its operators later pleading guilty to criminal violations of environmental law. Five years later, Rocky Flats sat unused and badly contaminated. The Department of Energy (DOE) called the site “one of the country’s most significant nuclear vulnerabilities,” projecting that cleanup would take 70 years and cost $36 billion.

That same year, DOE awarded management of the cleanup to Kaiser-Hill Co. DOE, Kaiser-Hill Co., the Rocky Flats Coalition of Local Governments, and a non-profit Citizens Advisory Board — which included community, activist, and government representatives — worked together to ensure the cleanup effort met the needs of the community and federal regulations. In 2000, Kaiser-Hill and DOE agreed to a second, unique “closure” contract, which fast-tracked site cleanup to be complete by December 2006.

Kaiser-Hill completed physical cleanup of Rocky Flats in October 2005, more than 50 years ahead of projections and 14 months ahead of the contracted target. Since 2007, the former nuclear weapons plant has been managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service as a National Wildlife Refuge, home to herds of mule deer and elk, along with the threatened Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse.

Read The Intersector Project’s complete case study on the Rocky Flats cleanup, “Turning a Former Nuclear Weapons Plant into a Wildlife Refuge.”

Build a Common Fact Base

As partners began working together to clean up Rocky Flats, the acceptable level of remaining soil contamination was a contentious issue. Since plutonium binds to soil, surrounding communities were very concerned about what remaining contamination would mean for future use of the land.

For the initiative to proceed with trust and consensus from partners, collaboration partners worked to Build a Common Fact Base — the agreement among partners on the facts that characterize the issue at hand.

DOE provided funding to concerned citizens’ groups so they could hire consultants to conduct their own research. Kaiser-Hill also conducted modeling assessments, as detailed as “how prairie dogs burrowing moved the soil.” Each organization shared their findings with one another, as well as committed to a two-year negotiation process to come to agreement on what contamination levels were tolerable at various underground depths. Nancy worked with her communications team to ensure that the information Kaiser-Hill provided was not only accurate and relevant to the discussion, but also presented in a format that made the highly technical information simple to understand to allow for informed decisions.

The Rocky Flats initiative illuminates the extent to which collaboration partners may have sector-specific biases that influence their determination of what facts are relevant to the issue to be addressed by the collaboration. Because agreement on a common fact base is critical to refining the collaboration’s understanding of the issue and honing strategy, the most successful collaborations facilitate processes through which partners can arrive at consensus on this point. Without such a process, partners may perceive that one partner’s perception of the issue is dominant over others and disinvest from the process. Rocky Flats provides an example of partners addressing this head on, leading to agreement and remarkable progress in a clean up of “one of the country’s most significant nuclear vulnerabilities.”