In 2004, after 50 years in operation, the Asheville Livestock Market in Western North Carolina closed its doors. Many local farmers then faced a difficult decision: continue raising cattle and absorb the increased cost of travel to buy and sell their livestock, or give up cattle farming completely. Bill Gibson, Director of the Southwestern Regional Council of Governments, feared that many would abandon their farms, allowing real estate developers to move in and damage the picturesque Blue Ridge landscape. Bill, along with L.T. Ward from WNC Communities, was called upon to develop a plan to build and operate a central livestock market, which would preserve the economic and environmental ecosystems of the region. L.T. Ward’s management and engineering expertise complemented Bill’s ability to build relationships and to rally the community. Through effective collaboration across sectors, Bill became the “seal of approval” in the pursuit of funding for a new market, connecting participants from all sectors at multiple levels. The Western North Carolina Regional Livestock Center (the “Center”) opened in Canton, North Carolina, in March 2011, reinvigorating the region and making small-scale livestock farming economically viable once again.

Rural Sustainability in Western North Carolina

About This Project

“We were in a community where the community worked together in a collaborative effort to make a successful project.”— L.T. Ward, Vice President, WNC Communities

Download this case study »

Both Bill and L.T. were born and raised in the Blue Ridge mountains. When the Asheville Livestock Market closed in 2004, Bill and L.T. had more than 60 years of combined experience brokering agreements and executing collaborative projects. Their leadership skills and professional networks were instrumental to the effort to establish a centrally located livestock market in Western North Carolina.

Prepared Mind

Before serving in Korea during the Vietnam era, Bill received a BS in Industrial Engineering from Western Carolina University (WCU). After working as an engineer in Atlanta, Bill returned to Jackson County in Western North Carolina, where he completed a Masters degree, focusing on personnel management. Around the same time, he joined the Southwestern Regional Council of Governments, a regional commission representing seven counties. Bill excelled at the Southwestern Commission, serving as Director from 1975 until his retirement in 2013. Bill approached his career with an open mind, and was willing to pursue opportunities and take on leadership positions across sectors. These experiences, combined with Bill’s ability to listen and learn from those he met, made him the ideal candidate to sell the idea of the Center. L.T., also driven by a desire to help others, took a more calculated approach in his career, constantly exposing himself to opportunities to build his management expertise and develop his interpersonal skills. As part of this process, L.T. sought out occasions to develop skills that would help him in areas such as accounting, financial management, project management, general management, and team building. Through these experiences, L.T. gained the skills and understanding that later helped him create the Center.

Integrated Network

The network and reputation Bill developed at the Southwestern Commission prepared him for one of the project’s biggest hurdles – funding. In his career, Bill worked with over 400 county commissioners, 50 mayors, and 700 members of city councils on developing projects that served the public interest in communities across the region. Bill was successful in facilitating fundraising from both private and public sources. As a result, when Bill approached grantors to support the Center, they were confident in both his judgment and his ability to deliver. L.T. also came to the process with a strong network of support, which he developed through his connection with WNC Communities. The WNC Communities structure emphasized grassroots involvement and included a number of sub-commissions that created resident associations for various activities, such as Beef Cattle and Dairy Farming. As a result of WNC Communities’ structure, L.T. was in a position to communicate with people at both the grassroots and leadership levels. His ability to effectively represent these interests and build relationships earned him the respect of those in the community, and gave him the legitimacy needed to approach partners to support the Center. Building on their trust-based, integrated networks, Bill and L.T. convened an impressive roster of participants from all sectors and at multiple levels. The involvement of these partners was integral to the project, and both Bill and L.T. credit the success of the Center to this collaborative effort.

Contextual Intelligence

Through his fundraising experience, Bill understood the requirements for securing public funding for the Center, such as nesting the proposed Center within a non-profit organization in order to receive public or quasi-public funds. To satisfy this requirement, Bill initiated the partnership with WNC Communities. Additionally, as he spent considerable time working with state legislators and government representatives at every level, Bill knew there would need to be a sufficient public interest in the project for officials to commit. Bill thus worked with partners to support a feasibility study on the economic impact that the Center would have on the region, and to articulate the interest and support of local farmers before approaching WNC Communities to move forward with the project.

Transferable Skills

When it came time to use the funds that Bill helped raise, L.T.’s ability to navigate the interests of the various stakeholders allowed him to manage the project effectively. Over the course of his career, L.T. worked in almost every aspect of project management, and collaborated with partners across sectors; he could facilitate their participation and account for any constraints they may have faced, such as internal bureaucratic processes or conflicting interests between parties. He likewise understood the issues that could derail or stall a project. Therefore, when designing a strategic plan for the development of the Center, and with the structure of the WNC Livestock Center LLC, L.T. drew on these experiences to identify ways in which the Center could deliver more efficiently. For example, when selecting an operator for the Center, L.T. developed a process that would satisfy representatives from the various counties affected by the Center, while also maintaining a sense of neutrality by allowing the Center’s Steering Committee to make the final design.

Build a common fact base

Bill and L.T. recognized the strain the closure of the Asheville Market had put on the community; in addition to the loss of income to individual farmers, the loss of profitability of small-cattle farms threatened to reduce the value of the farmland, as property taxes would likewise drop. Both L.T. and Bill understood the shift in property value could open farmers up to potential poaching from land developers seeking to capitalize on the picturesque location. To help farmers keep their land and preserve the cultural landscape, Bill and L.T. realized the need to show that they would be able to produce enough sales for a viable new livestock market. To do this, they supported a feasibility study which included surveys of over 200 local farmers designed to determine if there would be a positive net worth from the creation of a new cattle market. The results of this study quantified the economic impact that the closing of the Asheville Market had on the region, and signaled a necessary and financially viable opportunity.

Establish transparency of viewpoints

The development of the Center required a multi-million dollar investment involving a number of stakeholders from the government, private, and non-profit sectors. However, in the initial stages, there was concern among certain stakeholders that the Center did not fall within their traditional scope of funding. Of particular concern was the relationship between the Center and more traditional agriculture projects, which were generally under the scope of funders like the NC Tobacco Trust Fund Commission and Golden LEAF Foundation.

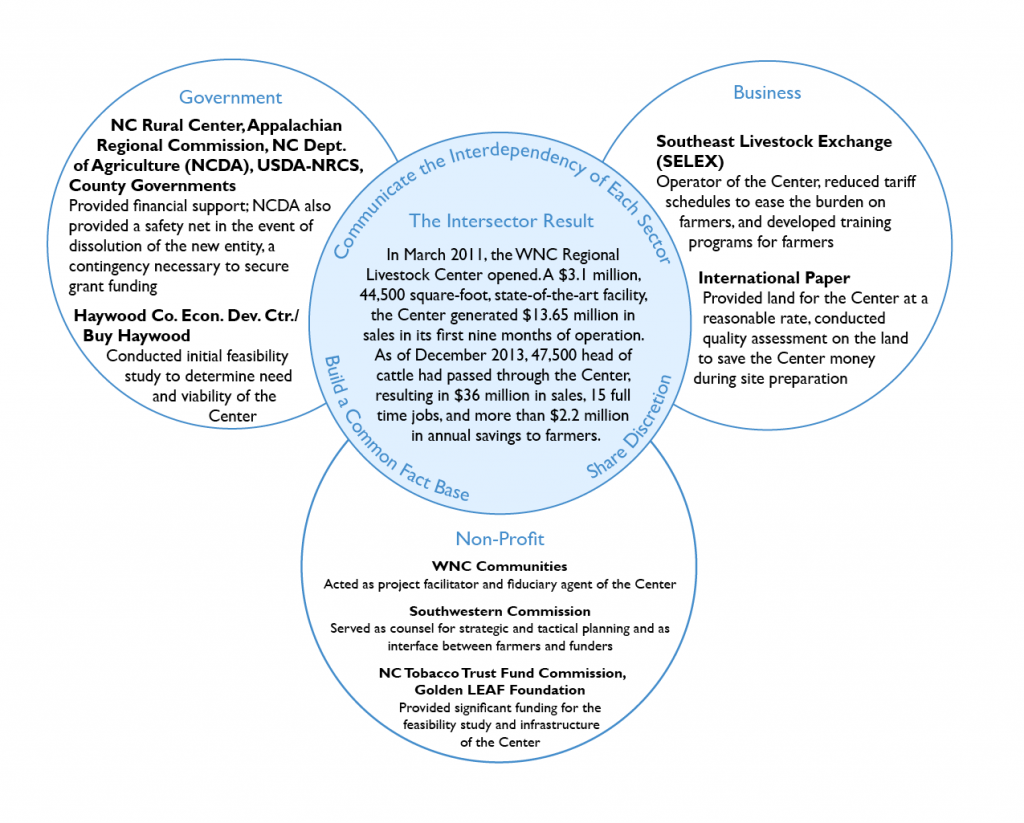

Communicate the interdependency of each sector

At a crucial turning point, Bill and L.T. brought all of the key stakeholders together for a presentation explaining the impact of the loss of the Asheville Market on the community, beyond just economic terms and the detriment to land values. Their presentation effectively communicated how the contributions from each party were essential to the collaborative effort, and allowed them to move forward with plans for the project under five categories: site location, facility design, funding, construction, and operational planning. On a pro-bono basis, L.T. acted as the Executive Vice President of the organization and managed each phrase of the project, such as overseeing the financial projections and providing financial reports, and ensuring that stakeholders were both confident in the importance of the project and engaged in the process.

Recruit a powerful sponsor or champion

One of the individuals present during Bill and L.T.’s pitch was North Carolina’s Commissioner of Agriculture, who was very impressed by the presentation. The support of the Commissioner’s office, his ability to facilitate funding, and his open endorsement of the project reassured other stakeholders of the strength of the Center, and eased concerns about the allocation of public and quasi-public funds. The Commissioner also offered his agency as a “safety net” in the event of dissolution of the new entity, a contingency necessary to secure grant funding. With the Commissioner’s support, Bill and L.T. avoided a potential collapse of the project in its critical early stages.

Manage expectations of process and results

L.T. managed the interests of each participant by predicting their “deal-breakers” and developing solutions that would produce favorable results for everyone involved. In particular, L.T. developed a clear plan that would account for the allocation of funds from each sponsor and prioritized the elements that were vital to completing the Center on the expected timeline. His ability to communicate progress throughout the construction process and present a clear, well-defined plan that accounted for potential set-backs and ensured that the development would continue reassured stakeholders of the viability of their investment. In addition to providing consistent progress reports to funders, L.T. engaged farmers who would be affected by the Center to ensure that their interests were represented as well.

Share discretion

While Bill and the Southwestern Commission were comfortable taking a lead role in raising the money, they recognized that the execution of the project would be better managed by WNC Communities, which had a strong history with a number of the stakeholders involved and had already been involved in the development of other regional agriculture projects. This arrangement allowed each organization to capitalize on its strengths – network support and fundraising for the Southwestern Commission, and project management and execution for WNC Communities – while creating a system that provided funders with security in their commitment.

The WNC Regional Livestock Center opened in Canton, North Carolina, in March 2011. Bill and L.T. raised the necessary funding to create the market, reviving the local economy and serving the needs of local farmers. As of December 2013, 47,500 head of cattle had passed through the Center, earning $36 million in sales and resulting in a total economic impact of more than $54 million. Achievements of the Center include:

- National award for collaboration from the National Association of Development Organizations (NADO), which “promotes regional strategies, partnerships, and solutions to strengthen the economic competitiveness and quality of life across America’s local communities.”

- 15 full-time jobs in operation.

- $2.2 million in annual savings to farmers by eliminating the additional financial burden of out-of-state livestock markets.

- Education and training opportunities to increase quality and revenue by supporting the North Carolina Beef Quality Assurance program, earning farmers more money by teaching them how to certify their own cattle.