Each year, approximately 300,000 people in the United States suffer a cardiac arrest while going about their daily lives. Known as an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in the medical community, survival rates have hovered around 8 percent for the last 30 years and can vary greatly between communities. When a group of health leaders in Atlanta considered the possibility of installing automatic defibrillators (AEDs) throughout the city to help improve survival rates in 2003, they quickly recognized that their inability to track the progress of OHCA patient outcomes through the medical system – from the ambulance to the hospital to the moment of discharge – would make it impossible to assess the effectiveness of such an investment. Dr. Bryan McNally, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine at Emory University, worked with Atlanta hospitals, emergency medical technicians, medical software providers, and a network of medical experts, to develop with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, design, and implement the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), the first database that tracks key details for OHCAs, such as whether bystander CPR was being performed and whether an AED was used. Following Atlanta’s 2005 implementation, CARES helped the metro area make significant improvements to its OHCA survival rates and responses. Today, CARES operates a nationwide registry that allows communities to track data and create reports to identify success factors, compare results to those in similar cities, and implement measures that can save more lives.

Improving Cardiac Arrest Patient Survival in Georgia

About This Project

Dr. Bryan McNally, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine at Emory University, worked with Atlanta hospitals, emergency medical technicians, medical software providers, and a network of medical experts, to develop with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, design, and implement the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES).

Download this case study »

Bryan began his career in emergency medicine as a paramedic in New York City. He completed his medical residency at hospitals in both New York and Boston, before earning a Master’s degree in Public Health from Boston University. His in-depth knowledge of emergency medicine, developed in a variety of healthcare settings, made him the perfect leader to communicate the importance and value of a community-wide cardiac registry system to the hospitals, emergency medical technicians, medical software developers, and non-profit organizations that were integral to the success of CARES.

Balanced Motivations

As a seasoned emergency medicine professional, Bryan had long witnessed “the end product of what happens when people get hurt,” from decisions like not wearing a seatbelt or motorcycle helmet. During his undergraduate studies, he lived in a firehouse, where he completed first aid and EMT courses, getting an early glimpse into the value of emergency medicine. His work as a paramedic in New York City after college stoked his interest in helping the community. He appreciated how easily qualitative emergency room experiences could translate into public health improvements if he could help communities access data that would show the connection between patient decisions, clinical care and eventual outcomes. These experiences with pre-hospital care led him back to school to earn his medical degree, giving him a thorough understanding of the complete patient experience during emergency medical events and the potential benefits of linking information throughout the care cycle.

Intellectual Thread

As a former EMS practitioner and an experienced emergency room doctor, Bryan understood the fragmentation of patient-care tracking between the time a paramedic team dropped off a patient at the hospital and the time the patient checked out. His firsthand knowledge of the time constraints and data collection methods of both paramedics and hospital staff helped Bryan focus on making sure CARES questions could be answered quickly and easily using existing systems. He also made certain that every question asked would “help provide a meaningful outcome,” keeping questions asked to a minimum to help ensure paramedics and hospital staff would participate. By focusing the project on achieving simplicity, easing burdens and providing community value, Bryan helped guarantee project success.

Contextual Intelligence

Bryan’s work in the emergency medical field gave him an understanding of existing data collection methods used during patient care. He knew that any system dealing with patient care would need to follow HIPAA, a set of regulations that address the security and privacy of health data, necessitating a complex system of safeguards to protect patient privacy. Understanding that only an experienced medical software provider could deliver such a system led him to develop the pro-bono collaboration with Sansio, a corporation that provides medical devices and software, thus ensuring a reliable software system that could be easily integrated into care providers’ existing routines. His understanding of business objectives led him to allocate the project’s “carry over budget” toward incentivizing Sansio to raise the priority of CARES software development so the project would stay on schedule. His experience with different communities’ emergency medical service systems likewise provided him firsthand knowledge of how levels of emergency care and results for OHCA events can vary between cities based on things like the depth of experience and long-term commitment to the field of its paramedic team. He readily understood the value a cardiac registry system could provide in helping to demonstrate the effectiveness of early OCHA interventions like bystander CPR and use of AED in improving outcomes.

Transferable Skills

Bryan cultivated a team of emergency medicine leaders to help inform the development of the registry. Two mentors at Boston Emergency Medical Service, Dr. Larry Mottley and Dr. Peter Moyer, helped Bryan recognize the importance of collecting basic outcome measures as “the first step in performing a quality improvement program” to raise the standard of clinical care. This provided a deep understanding of the potential value of the CARES registry to the community. Drawing on his knowledge of their research and interest areas, he sought out a relationship with Dr. Mickey Eisenberg, a pre-hospital cardiac arrest expert, later ensuring he contributed to the definitions and data dictionary that would form the basis of the CARES development process.

Share a vision of success

Early in the project, collaborators agreed that the goal was to “develop a cardiac arrest registry that collected basic outcome data” on patients who experienced OHCA in order to help improve the standard of care in the community. This agreement proved to be crucial to the program’s overall success because it necessitated the development of simple questions that would generate meaningful responses and could be easily answered by medical practitioners. The vision helped guide the development of simplified medical definitions for use within the system, which made it easier for EMTs and hospital staff to participate, and resulted in the community having a better measure of its performance.

Demonstrate organizational competency and an ability to execute

Representatives and members of the National Association of EMS Physicians helped CARES to develop the standard definitions and data dictionary that would guide questions and responses about the types of resuscitation efforts taken and the resulting cardiac rhythms observed by practitioners in the field. Several of these doctors were simultaneously working to standardize EMS terminology for other organizations, so the project benefited from insider information on the direction it should take. Sansio, a private industry partner with medical software expertise, HIPAA compliance knowledge and existing infrastructure to support data collection and reporting, oversaw the development of software that would be used to collect and report data.

Build a common fact base

CARES benefited from a well-documented need for the ability to track results of OHCA care and a common desire to improve patient outcomes. Medical journals had long documented fluctuations in OHCA survival rates between different cities, and a highly visible USA Today study in 2005 suggested that “inconsistent record-keeping” made it impossible for poorly performing cities to identify measures that might improve survival. During an initial meeting in 2003, Dr. Arthur Kellermann of Emory University raised these issues when Atlanta was considering investing significant philanthropic funds into place AEDs throughout the city, explaining that leaders would have no way to tell whether the funds resulted in lives saved. The American Heart Association, which has set a goal of doubling OCHA survival rates by 2020, recognized that the ability to track OCHA outcomes and intervention results would underscore the importance of interventions it supports, like bystander CPR training and public access to AEDs, while helping communities make decisions that would save lives. The CDC recognized this potential for improved community health, and decided to fund the program.

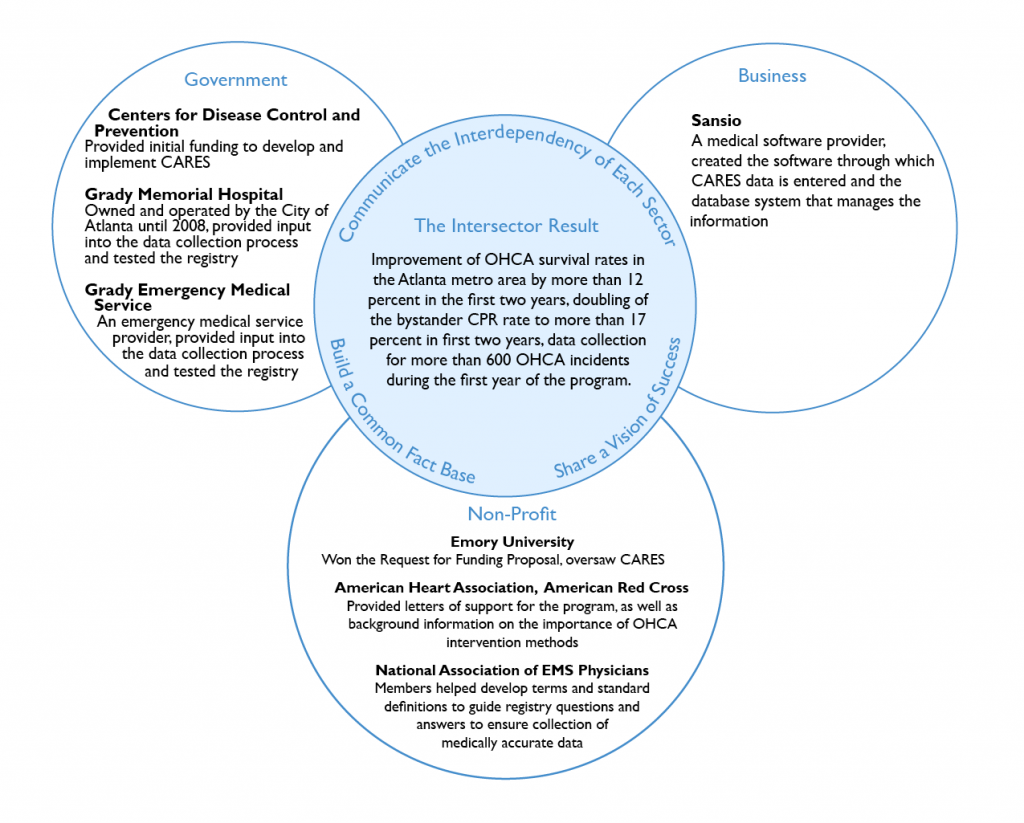

Communicate the interdependency of each sector

Sectors understood how their specific contributions could help create a registry that could improve public health. Hospitals and EMS providers were the only ones who could document the patient care details that were integral to the program’s success, while providing feedback that would ensure CARES adoption would be a simple choice for all care providers. Hospitals, where time is extremely limited, donated time and attention to the project and provided necessary emergency medical service knowledge because they understood that their participation would have a direct impact on improving community health: “without the outcome from the hospital, we don’t have a meaningful measure.” Sansio understood that this patient care data would be meaningless if it couldn’t be easily tracked and retrieved by participating communities, and that the company’s participation could help grow its business once the system expanded across the country. Its software development expertise helped to ensure the program’s success.

Recruit a powerful sponsor or champion

The involvement of Dr. Arthur Kellermann, founding chairman of the department of Emergency Medicine at Emory University and a frequently published expert on public health policy, brought credibility to the CARES program. His connections in the medical community, non-profit, and business sectors helped ensure that the right collaborators would contribute.

CARES has helped Atlanta track and measure improvement in patient survival rates throughout the City of Atlanta track, which rose from less than 3 percent in 2005 to 15 percent in 2007. The first-year results of the CARES pilot program clearly showed Atlanta’s poor performance in saving the lives of cardiac arrest victims and provided a baseline from which to make improvements. Armed with credible data, Mayor Shirley Franklin made improving the city’s results a priority. She recognized the city’s low rates of early OCHA interventions like bystander CPR and AED use, and made CPR training mandatory for the city’s 8,000 employees. CARES also provided a clearer picture of emergency response times within the community, which Atlanta to remove a step from the ambulance dispatch process, shortening wait times by about 1 minute. Today, CARES tracks OHCA data in communities that cover 25 percent of the American population. Contra Costa County EMS in California has used CARES to identify decreased OHCA survival rates in low-income communities and design health interventions to address these groups. Since joining CARES in 2007, San Francisco has achieved a 23 percent OHCA survival rate, up from 9 percent when it began tracking data.

- Since 2005, CARES has expanded to include communities nationwide, including 13 statewide registries and communities in 16 more states.

- In 2012, funding for CARES transitioned from government, through the CDC, to private funding. As of 2014, the program was funded by contributions from non-profits the American Heart Association and American Red Cross; along with Medtronic Foundation, a joint effort of medial technology company Medtronic’s business and philanthropic divisions; medical products company ZOLL Corporation; and in-kind support from Emory University.

- In addition to tracking paramedic and hospital data, CARES now tracks data related to 9-1-1 calls and emergency dispatches, providing further insight into a community’s overall OHCA response.

- In 2009, CARES developed an international partnership with the Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS), which represents Dubai, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Turkey.