The Elizabeth River, 23 miles of estuary on the southern end of Chesapeake Bay, has one of the busiest commercial ports in the world. A history of industrial pollution, however, contributed to sediment contamination and “toxic hotspots” along the river. In response, Marjorie Mayfield Jackson helped launch the Elizabeth River Project in 1993 to “restore the river to the highest practical level of environmental quality.” Its 2003 “State of the River” report highlighted a particular hotspot in the southern branch of the river at Money Point, where, for decades, wood treatment facilities allowed creosote to pool on the river floor; the study showed cancer rates of 38 percent and precancerous lesions of 83 percent among the small mummichog fish. As Executive Director, Marjorie spearheaded the cleanup of Money Point, collaborating with industries, citizens, and governments. Their joint efforts helped to lower cancer rates among the mummichog to less than seven percent in the initial cleanup area. Stakeholders have worked collaboratively on dozens of other projects, including reducing future pollution and restoring wetlands, setting a goal for the entire Elizabeth River to be both swimmable and fishable by 2020.

River Restoration in Virginia

About This Project

“When everybody’s heard, there is almost always some place where there is a common ground… If you can listen to each other you can find that you can act out of that to make great plans. But you need a process to discover it.”— Marjorie Mayfield Jackson, Executive Director, The Elizabeth River Project

Download this case study »

Marjorie began her career in journalism, working for the Virginian Pilot in Norfolk. After taking a sabbatical from the newspaper, Marjorie founded a non-profit organization to address the health of the Elizabeth River.

Balanced Motivations

Marjorie grew up in the South with a deep appreciation for the natural environment and, in particular, “the restorative qualities of rivers.” In her mid-thirties, while studying for a Masters in lay ministry, she began a process of reflection on moral choices, and felt pulled away from journalism towards advocacy work. Living on the Elizabeth River, she knew the environmental damage firsthand; she knew that, as a community, they could “do better.” Encouraging people to do right by the environment, rather than policing them, gave a collaborative focus for the organization.

Transferable Skills

To bring the Elizabeth River back to health, Marjorie relied on the knowledge and skills she had developed as a journalist. At ERP’s inception, she and other founding members conducted 65 interviews with stakeholders in the community to measure willingness to participate in river clean-up efforts. Her ability to listen, a crucial skill in journalism, allowed Marjorie to hear and incorporate the various concerns from participants. Her writing and data collection skills gave her a means of organizing and disseminating information on the status of the Elizabeth River.

Contextual Intelligence

Marjorie’s journalism career also gave her an understanding of the ways that other sectors worked and prioritized. When reaching out to businesses along the Elizabeth River, for example, she was able to understand how the cleanup would affect them, and then frame the benefits of the project to address these sensitivities.

Integrated Networks

While the river restoration project required that Marjorie build a new network of regulators, scientists, and citizen activists, her career as a journalist made her familiar with the key political players in the area and moreover, had made her comfortable contacting them.

Intellectual Thread

As a journalist and resident, Marjorie was well aware of the extent of the pollution of the Elizabeth River. Her years of involvement with the Elizabeth River Project, combined with her personal passion for the river itself, gave her subject-matter expertise.

Prepared Mind

Marjorie’s departure from journalism to found the non-profit and focus on advocacy showed a willingness to seize new opportunities. Her passion to see the Elizabeth River brought back to health was propulsive and successful.

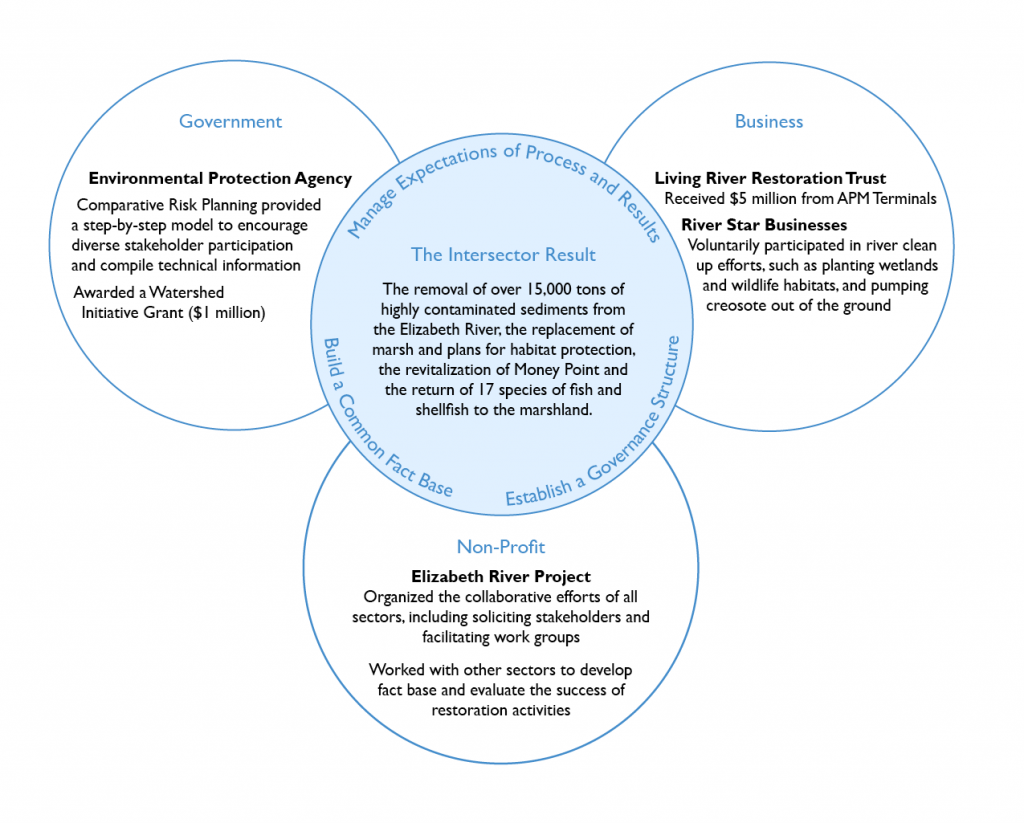

Establish a governance structure

The Elizabeth River is one of the most industrialized rivers in the country, home to both the world’s largest navy base and its largest coal exporting facility. In this environment, Marjorie knew that if she took a confrontational/regulatory approach, she would be no more than a “little mosquito on the edges.” She decided instead to collaborate with the private sector and focus on partnership development. An initial advisory board of thirty, representing all stakeholder groups, gathered to discuss ways to educate the public and create consensus.

Build a common fact base

Building on a philosophy of finding common ground through win/win solutions, Marjorie focused on how all three sectors would benefit from restoration: non-profits would save the river, government would serve its citizens, and business would avoid costly lawsuits and improve employee morale. The Watershed Action Team, formed under the guidance of the EPA’s Comparative Risk Office, helped the Elizabeth River Project facilitate consensus while listing the river’s worst problems. A group of 120 people divided into working groups to rank problems, exchange rankings with other subgroups, and then listen to counter arguments before finally reaching an agreement. Through skilled facilitation, the Watershed Action Team was an effective tool in reaching consensus on facts about the river’s most pressing problems. This led the team to agree on the primary focus of the ERP cleanup efforts – “the goo must go.”

Recruit a powerful sponsor or champion

From 1995 to 2003, Ray Moses, former Admiral of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), was the President of the Elizabeth River Project. His connections with business, city, and federal leaders as well as his environmental expertise brought credibility and legitimacy to the Project. The Project also benefited from the support of the four mayors in the four cities that make up the Elizabeth River watershed – Norfolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake and Virginia Beach. All the city’s mayors sat on the original Leadership Review Board and endorsed the original watershed action plan. The mayors likewise cost-shared a Corps of Engineers project to restore wetlands and plan for sediment cleanup on the river.

Manage expectations of process and results

The Elizabeth River Project and collaborators revised the initial 18-point plan for river restoration multiple times since the initiative began. Revision occurs every six years and is informed by developments along the way. This maintains interest and engagement in the process, and ultimately allows for a more informed and focused program to effectively allocates resources.

Demonstrate organizational competency and an ability to execute

The Elizabeth River Project organized all efforts and led the offshore environmental cleanup; Marjorie had an idea of what each participant could bring to the table. The City of Chesapeake improved storm water controls on a main road, while the federal government helped with funding and the state with monitoring. The “River Stars Businesses” coordinated and delivered goods, services and equipment to handle specific on-the-ground responsibilities. Rather than remaining reliant solely on EPA Superfund enforcement, the voluntary collaboration with industries and government enabled a record quick timeframe and a reduced cost to businesses.

The Elizabeth River Project’s collaborative clean-up effort resulted in a substantial improvement in the health of the river. The Project helped remove 36 million pounds of PAH contaminated sediment at Money Point; the cancer rates among the mummichog have dropped to less than seven percent in the initial clean-up area, indicating a significantly better environment for these fish, and a healthier ecosystem overall. Additional reports show that more than twenty species of fish have relocated along the river, as well as families of river otters, who do not settle in polluted waters. The ERP projects that, given early successes, the Elizabeth River will be both swimmable and fishable by 2020. Continuing efforts include:

- The presentation of River Stars Pollution Prevention and Stewardship Award for industry, highlighting the efforts of local business.

- The opening of Paradise Creek Nature Park, a 40-acre nature park, that showcases forested shore revitalization and wetland restoration in partnership with the City of Portsmouth.

- In 2009, launched “America’s Greenest Vessel,” the Learning Barge, a steel barge with a live wetland on board. The 120 foot barge has hosted more than 20,000 students.

- In 2011, the Elizabeth River Project expanded stakeholders to include homeowners along the Lafayette branch of the Elizabeth River; The 1,700 homes in the River Star Homes program are committed to seven steps, including modeling “lawn makeovers” to reduce fertilizer dependence.