The shortgrass prairie of Colorado is the state’s largest and most diverse ecosystem, host to over 200 plant and animal species across 27 million acres of land. A 1998 study by The Nature Conservancy showed that this ecosystem faced pressures from the development of Colorado’s highway infrastructure as well as private farm practices. While mitigation and land conservation efforts were already in place, analyses failed to achieve the scale necessary for a comprehensive evaluation that would improve the ecosystem. In 2000, a group of scientists and governmental agencies confirmed this threat and explained that a lack of land conservation had led to the decline of over 100 species, with 33 candidate and “at risk” of extinction. Marie Venner, from the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), quickly recognized the opportunity for a conservation partnership that would incorporate disparate interests and rectify the technical deficiencies of piecemeal evaluations. She chose to partner with Edrie Vinson of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Chris Pague from The Nature Conservancy (TNC), representatives of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and landowners of the affected lands. Together they assessed effective conservation of the shortgrass prairie while allowing continued highway infrastructure development and farming.

Conserving the Shortgrass Prairie of Eastern Colorado

About This Project

“While shortgrass prairie issues can be challenging, long-term conservation success will require an open and honest dialog among public agencies, private landowners, and non-profit partners. The land management entities in this MOA will foster a collaborative approach to shortgrass prairie conservation and management and are committed to working with local communities.”– Shortgrass Prairie Initiative MOA

Download this case study »

Marie, CDOT’s Natural Resources Unit Manager, recognized that shortgrass prairie conservation could be an opportunity for multi-sector cooperation. It could also produce tangible benefit for “at risk” species. For this reason, she partnered with Chris Pague of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the Colorado National Heritage Program to conduct a large scale species conservation needs assessment. Marie’s dedication to conservation and years of success with collaborative governance shaped her vision of a cross-sector approach.

Balanced Motivations

Marie had always been passionate about serving the public good by protecting the environment. She accepted jobs as a state employee and as a private contractor, adapting her role in order to contribute to both environmental conservation and the efficient use of public resources.

Intellectual Thread

Marie’s focus on the environment began during her academic career. After graduate school, she had technical training in facilitation and the management of natural resources. Although the Shortgrass Prairie Initiative was her first environmental conservation project, she had over a decade of combined professional and academic experience researching environmental challenges of different ecosystems.

Contextual Intelligence

Marie’s previous experience with TNC, two state Departments of Natural Resources, and the Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, gave her an understanding of the government and non-profit sectors. Combined with several years of experience as a private consultant, Marie knew how each sector approached the management of natural resources and ultimately how best to approach the collaboration.

Prepared Mind

Her work in different areas of environmental conservation meant Marie was used to looking at one problem from many different perspectives. She had functioned as contractor, research partner, and collaboration leader before, for instance working for the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) in Georgia, in partnership with The Nature Conservancy (TNC). Eager to work in environmental protection, Marie adapted quickly to new roles.

Transferable Skills

Marie’s pioneering work in programmatic approaches for interagency cooperation allowed her to coordinate the multi-party efforts involved in preserving the shortgrass prairie. Her training as a facilitator in dispute resolution developed her capacity to broker win-win solutions while reconciling divergent interests. Over the course of her career, she honed writing and analysis skills to communicate the impact of infrastructure on different ecosystems. Finally, Marie’s time as a consultant equipped her with the research skills to quickly grasp key conservation challenges.

Integrated Networks

Marie spent her career building a reputation as an expert in infrastructure mitigation, developing extensive experience in the environmental field. Prior to the collaboration, Marie worked with the Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, as a contractor, and for the Georgia DNR, with TNC and the Altamaha Bioreserve. This gave her a wide range of contacts, notably Edrie Vinson and Chris Pague, who provided further legitimacy and the support Marie needed to move the collaboration forward.

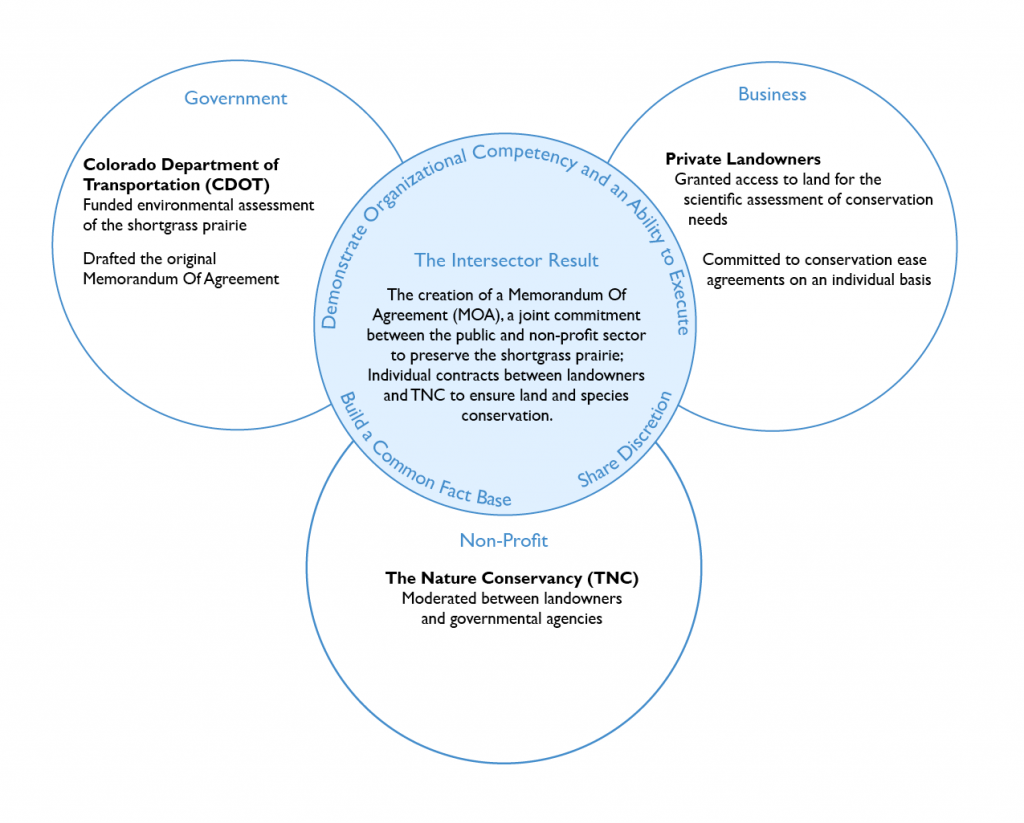

Share discretion

Collaboration partners, including landowners and representatives from the public sphere, met at least once a month. They assigned tasks according to the capacities and expertise of each partner and, notably, worked without an external facilitator. The result of their deliberations, outlined in the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA), created more efficient conservation activities to sustain native species and ecosystems.

Establish a governance structure

The collaboration was led by the Shortgrass Prairie Partnership, a small interagency group of experts. Although the non-profit and public sectors assumed larger responsibility by contributing research and funding, the success of the project depended on the commitment of the private sector, specifically the landowners who owned 86 percent of the endangered land. Landowners agreed to place easements on their affected property in cooperation with the terms set forth in the MOA.

Build a common fact base

In addition to prior descriptive data of the region by the USFWS, the team built on previous research by TNC, the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP), and the Colorado DNR Division of Wildlife. Then, over a two year period, a group of almost two dozen land managers, landowners, state and federal agency representatives, and scientists agreed on the need for a study of the shortgrass prairie. From the subsequent study, they concluded that 44 percent of Colorado’s shortgrass prairie (24 million acres) was under severe pressure.

Demonstrate organizational competency and an ability to execute

It was crucial that all parties were respected and established professionals in their fields, with the support of their agencies. Their credibility facilitated communication and the negotiation of a unique and context-specific approach. The partners also agreed to work for and benefit all stakeholders, in addition to the species and habitat in question. The CDOT and the USFWS anticipated cost and timesaving, and CDOT funded a mapping of the species and ecosystems of the shortgrass prairie. The CNHP and the USFWS from the non-profit sector provided important scientific information and a steadfast commitment to the conservation of biodiversity. Finally, landowners were incentivized to negotiate land easements as well as change farming practices to better respond to specific ecological needs of an affected area.

Communicate the interdependency of each sector

The vision of and commitment to win-win solutions for all partners was fundamental to the success of this process. Inclusive meetings developed trust between participants, and allowed the group to reach consensus and eventually legally binding agreements. Landowners limited their land use to practices compatible with conservation efforts, and since landowners trusted TNC’s incentive to participate, TNC assumed the role of mediator between the public and the private sectors.

Marie and her collaborators crafted a Memorandum of Agreement to outline the aims, roles, and responsibilities of each partner. Additionally, binding agreements between the TNC and individual landowners ensured shortgrass prairie conservation on private property. The collaboration was a pioneering success: the state department drafted the MOA, an NGO became the mediator between state agencies and private landowners, and private landowners agreed to collaborate rather than merely partner in exchange for financial incentives. The Shortgrass Prairie Initiative and the MOA managed to conserve over 70,000 acres with an additional 34,000 acres pending easement, eventually exceeding their target conservation goal.

- In signing the MOA, the collaboration partners agreed to protect the shortgrass prairie lands for twenty years (until 2023), an agreement with potential for extension.

- The model of collaborative land conservation continues to be implemented by state departments in other projects and has gone on to win awards, including the Environmental Excellence Award in 2003.

- Private landowners have endorsed the idea of easements, encouraging neighboring farms to adopt similar practices.