In the early 2000s, community and technical colleges in Washington State began to observe a troubling trend: many students enrolled in basic skills programs were not advancing towards acquiring the credentials necessary to advance to college-level programs or secure employment. The Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) set out to resolve this problem with the aid of Tina Bloomer, a workforce development professional from the Spokane community college system. Working with a team at SBCTC – which comprised representatives of the workforce development, basic adult education, and finance departments, as well as employees from community colleges statewide and local workforce leaders – Tina created a program that allows students to benefit from a combined educational stream incorporating technical and professional content into basic skills and education courses such as Math, Science, and English as a Second Language. The innovative Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training program (I-BEST) has helped to “increase the rate at which adult basic skills students advance to and succeed in college-level occupational programs.” The I-BEST instructional model helps students succeed in college-level coursework and gain Associates Degrees. These improved credentials help them to earn between $13-15 an hour in in-demand fields throughout the region. Evidence suggests that I-BEST students are likely to outperform non-I-BEST students in traditional basic skills programs, nine times more likely to earn a workforce credential, and three times more likely to earn college credit.

Strengthening Basic Skills Education in Washington

About This Project

“You often find when a person has knowledge and experience working in different sectors, it gives them the language that allows them to talk across the sectors more easily.”— Tina Bloomer, Policy Research Associate, Washington State Board for Community & Technical Colleges

Download this case study »

Tina joined the State Board in 2004 during the preliminary planning stages for I-BEST. Thanks to her experience working at the Community Colleges of Spokane, which had among the largest adult education and workforce education programs in the state, she understood how such programs worked and where they could intersect with the community college system. When SBCTC appointed an agency lead for I-BEST in the program’s second year, Tina was selected; she served in that position for four years, helping to shape the program into what it is today.

Prepared Mind

At the time she joined SBCTC, Tina had almost ten years of experience working in education administration. She had been approached by both the director of workforce education and the director of basic adult education to join their divisions, but accepted an offer to be the Director of Student Achievement Projects since she believed that a program targeted at helping low skilled and underserved students in community and technical colleges encompassed the aspects of education that were most important to her. The move enabled Tina to transition into the public sector and to work at the policy level on issues with which she had been confronted in the Spokane community college system. During the early phases of I-BEST preparation, Tina worked out of SBCTC’s Overall Education Division, in which the workforce education and basic adult education departments were housed. Her experience in Spokane and her work on the Student Achievements project allowed Tina to function as a cross-silo person within the division.

Intellectual Thread

Prior to her position at SBCTC, Tina worked within the Community Colleges of Spokane District as an Associate Vice President for Workforce Education and as a Welfare to Work Project Manager. She had five years of experience in basic education and three years in workforce education, and was knowledgeable about federal and state policy issues as well as the culture of the school system. Her knowledge of adult education programs enabled Tina to appreciate the barriers that adult education students face, such as not having school IDs or access to school facilities. She likewise understood the tracking system for community college funding and how it could be useful in designing the I-BEST program. Aware that community colleges needed to “meet a full-time equivalent quota” for funding, Tina applied her knowledge of data and tracking systems for students and school funding that would motivate the schools to participate.

Transferable Skills

Tina possesses a number of skills that allowed her to design a viable program. She engaged her analytical skills to conduct qualitative research for the pilot programs, working alongside quantitative researcher David Prince. Her experience in the IT and healthcare industries gave her knowledge of workflow, quality control, and operations management. Her budgeting skills and knowledge of financial aid in the community college environment allowed her to address the hurdle of coding and funding for I-BEST, which did not fall into “neat boxes”. Tina and her team created an evaluation tool for the reviews and site visits of the pilot projects, but she understood that, to design a strong program, they also had to listen carefully to the people running the programs. Her prior experience administering both workforce development and basic education programs allowed her to engage in a meaningful way with the school teams, while her analytical abilities enabled her both to ask questions of what was working and to observe what was missing.

Contextual Intelligence

After she received her MBA, Tina worked in IT and in healthcare before joining the technical and community college system in Spokane. As Computer Lab Manager for the Adult Basic Education Division, she drew on her business experience to design effective programs, gain valuable funding, and communicate effectively with the local Employment Security and Private Industry Council. Tina channeled her understanding of the business sector into the I-BEST planning process. As Welfare to Work Projects Manager, she managed grants and programs with funding from the Department of Health and Social Services, Employment Security, Department of Labor, and SBCTC. At Spokane Community College, she served as Interim Associate Vice President for Workforce Education, in which capacity she was responsible for programs including Perkins, WorkFirst, and Worker Retraining. This responsibility for federal and state programs at the college level gave Tina direct experience in interpreting policy and understanding state funding.

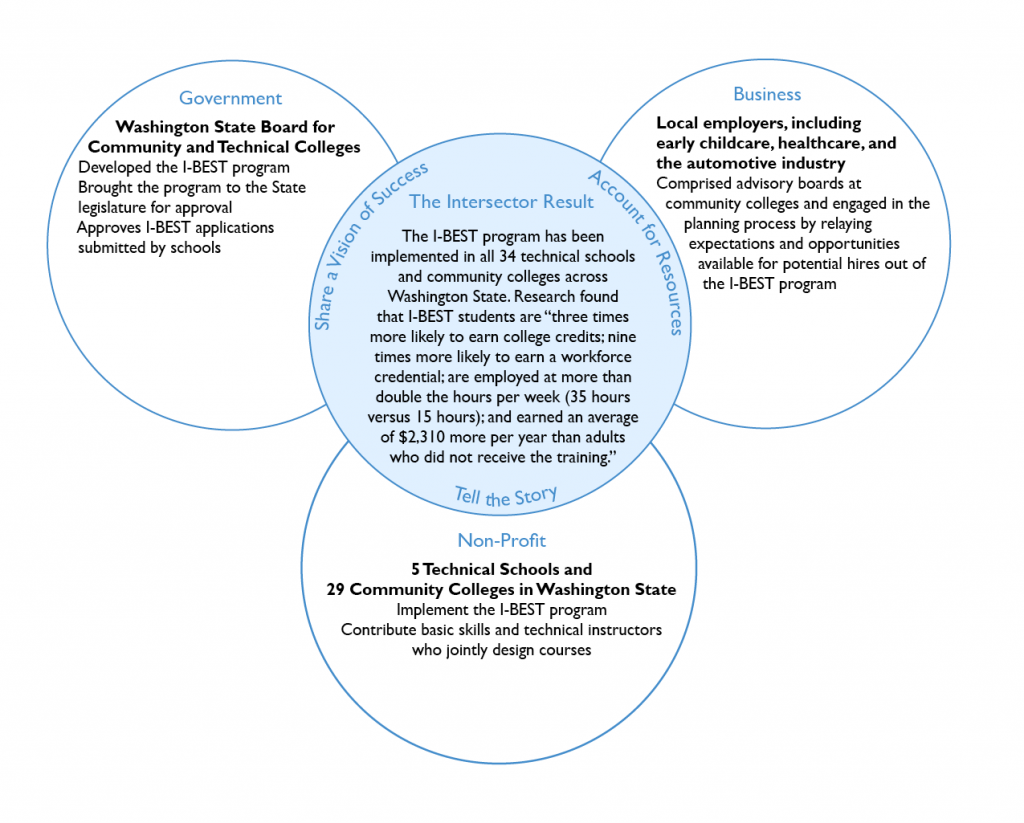

Account for resources

Resources from all sectors had to be taken into account for this collaboration to come together. The college system needed to identify which teachers from both adult education and workforce development departments could teach jointly. The creation of an administrative staff was arranged according to each college’s needs, although staff members typically came from the basic skills department. The interdepartmental nature of the program required coordination between an array of departments from education to financial aid, leading many schools to appoint a dedicated I-BEST coordinator. In addition to staff, funding for I-BEST has been an ongoing consideration. The program is funded by the State of Washington, but some schools seek additional support. The regional labor market’s demand for technical training graduates had to be assessed in order to ensure that graduates would enter into professions with a base pay of $13-15 per hour.

Share a vision of success

SBCTC held a series of meetings with members from participating community college offices including student services and administration, and departments including technical and adult basic education. These meetings also included SBCTC staff from the adult basic education division, the workforce education division, and the student services division. The priority was to encourage day-to-day operational staff to discuss and reach consensus on critical aspects of the program. Among the issues discussed were the need for two teachers in each classroom – an adult basic education and a technical teacher – to overlap for 50 percent of class time; that learning outcomes and curriculum had to be jointly developed by the two teachers; that the involvement of student services was crucial for the program’s success; and that credit earned for students had to be given college level accreditation. Results from these conversations, which were crucial to the pilot program, were incorporated into the national model.

Build a common fact base

Community colleges had tried different approaches to improve the results of adult basic education courses, but it was clear that something more comprehensive than what had previously been attempted was needed. There were various grants and funding streams that separated initiatives across schools focused on improving adult education programs and student achievement levels. SBCTC convened a panel of education experts together with the Boards’ Workforce Education Council and Adult Education Council to discuss how community colleges could better prepare students for further education and the workforce. The group agreed on the issues that the pilot program needed to address, including the de-marginalization of Adult Education programs. The Board funded ten pilot programs between 2004-2005 to test different approaches to improve basic education outcomes. I-BEST resulted from an evaluation of the outcomes of each of the ten pilot programs.

Tell the story

The I-BEST program has become a model for community colleges and technical schools nationwide. With funding from Jobs for the Future, private foundations, and other states interested in the program, Washington’s community and technical colleges have provided support to 20 states hoping to implement similar programs. The SBCTC website shares research on I-BEST, including external reviews of the program from the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. SBCTC personnel have conducted outreach for the I-BEST program as well: in 2008, Tina published an article in the October “Literacy Update” for the Literacy Assistance Center outlining the rationale behind I-BEST; in 2009, members from SBCTC spoke in Washington D.C. about I-BEST as part of governmental hearings supporting the renewal of the Workforce Investment ACT. Additionally, many news outlets have covered I-BEST, including The Atlantic (March 2014).

I-BEST emerged from the best practices of ten programs piloted in Washington State. The program improves the career prospects for basic education students, often the most left-behind in the community college system. I-BEST is implemented in all 34 technical schools and community colleges statewide. It has received nationwide recognition as an effective way to improve adult education by incorporating technical and professional content and preparing a more skilled workforce for in-demand careers in industries such as healthcare, early education, and the automotive industry:

- I-BEST was named a ‘Bright Idea’ by Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government in 2011 and is being replicated and implemented across the country. At least 20 states have received assistance from SBCTC to implement similar programs, including Minnesota, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Alabama, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Rhode Island, and Texas.

- Students are seeing better results from their experience. I-BEST students are three times more likely to earn college credits and nine times more likely to earn a workforce credential.

- I-BEST students earned an average of $2,310 more per year than their peers who did not receive the training.