In New York, the energy used in buildings is a major source of pollution, accounting for about 75 percent of the city’s overall greenhouse gas emissions and impacting public health. Air pollutants such as nickel, soot, and sulfur dioxide contribute to an estimated 3,000 deaths annually in New York City, according to the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. In 2007, soot emitted by New York City buildings burning residual fuel oil – No. 4 and No. 6 oils – caused more fine particulate pollution than all of the vehicles on the city’s streets combined. To combat this, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) issued regulations requiring that buildings convert to cleaner fuels from heavy heating oil beginning in July 2012. But because of perceived market hurdles, the deadline for some of the dirty fuels stretched out to 2030. To overcome these barriers, the City of New York, EDF and other partners created the NYC Clean Heat program, which led to one of the fastest and most significant air quality improvements in New York City history. The campaign united action by government, utilities, banks, real estate leaders, and non-profits to help buildings convert their boilers to a range of cleaner options, including natural gas, ultra-low sulfur No. 2 oil, and biodiesel. NYC Clean Heat’s collaborative efforts helped deliver dramatic improvements: a 69 percent reduction in sulfur levels, a 35 percent reduction in nickel levels, and a 23 percent reduction in soot levels in the city’s air.

Returning New York City Air Quality to the Highest in Fifty Years

About This Project

“NYC Clean Heat is a practical, high-impact solution that serves as a model for cities around the world, proving that big environmental gains are possible when government, finance, real estate and advocates join forces to achieve a common goal.”— Andy Darrell, New York Regional Director, Environmental Defense Fund

Download this case study »

In 2008, while looking out the window of his office at the Environmental Defense Fund, Andy Darrell and his colleague Isabelle Silverman saw a cloud of thick black smoke emanating from a nearby building. As the New York Regional Director of EDF – a non-profit that seeks market solutions to environmental challenges – Andy realized that he and his colleagues could do something about it, but it would take collaborative effort across government and the private sector. The EDF team reached out to stakeholders from government, business and other environmental organizations, and helped shape a joint solution to what they saw as a pressing danger to public health.

Balanced Motivations

Andy’s passion for the environment began with his first ecology project in New York City, the Hudson River Park redevelopment. This five-mile waterfront park in western Manhattan maintains a unique balance of commercial and recreational activity. This experience ignited Andy’s enthusiasm for solving environmental challenges in ways that work for quality of life and for the bottom line – he sees cities as part of the natural environment, with the possibility for infrastructure to improve the environment. Andy’s passion for the Clean Heat project stemmed from a broader reflection on how NYC residents use energy, and how the project could both improve local living conditions and serve as a model for collaborative problem-solving in cities.

Intellectual Thread

Andy’s background in clean energy, as Chief of Strategy for EDF’s US Climate and Energy program, brought subject expertise and strategic insight to his leadership of the Clean Heat collaboration. He saw the role that buildings can play in leading transition to clean energy, and his experience with the Park led him to look at the impacts that these buildings have on air quality very locally – looking at the air quality in neighborhoods near buildings burning specific fuels. This insight was key to the success of Clean Heat. Prior data collection measured regional averages, failing to identify levels of pollutants ingested on a day-to-day basis. Evidence that pollution in areas burning high levels of residual fuels was greater propelled the collaboration forward.

Contextual Intelligence

Having worked as an energy consultant, Andy understood the unique resources New York City’s business community brought to the table. He also understood the potentially large-scale social impact those resources could support. Andy’s served in the public sector as an advisor for Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030, where he learned about the city’s effort to improve air quality in New York City through strategic policy. This experience gave him a multi-faceted perspective in his work leading the Clean Heat initiative.

Integrated Networks

Andy had earlier reached out to the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) to encourage them to conduct a study measuring levels of air pollutants in specific neighborhoods across the city. This study proved valuable: the findings of DOHMH confirmed the threat to public health. Andy’s prior relationships in government and the private sector helped him motivate stakeholders to move forward quickly with collaborative efforts — “When you build a relationship of trust on one issue it can translate into the ability to open the door for a conversation about another.” Equally important, Andy helped mobilize a broad team inside EDF, across science, media, law and project management, bringing on board Mary Barber and Abbey Brown to add management expertise as the program grew from an idea hatched looking at pollution out the window to one of EDF’s largest city-based initiatives.

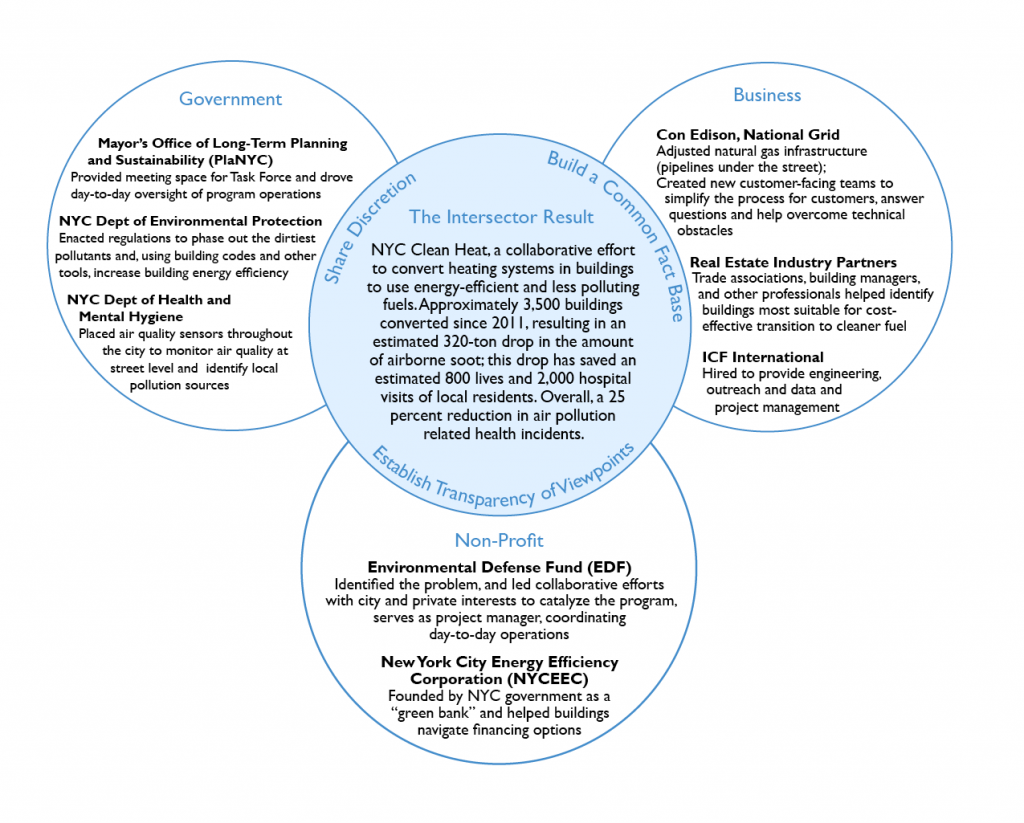

Build a common fact base

Andy and the EDF team analyzed the source and extent of the black smoke emanating from buildings across New York City, which prompted EDF to commission a report, “The Bottom of the Barrel”, released in December 2009, exploring precisely how buildings burning residual fuels produced high levels of harmful emissions and the effects of the black smoke on public health. Independently, DOHMH had been conducting an air quality survey called the NYC Community Air Survey (NYCCAS) which released a report around the same time. DOHMH and EDF jointly recognized that the issue of heating oil was the largest factor affecting air quality in New York City. Approximately 10,000 buildings throughout the city were burning No. 4 and No. 6 oils, and the areas with the highest levels of sulfur and soot pollution corresponded to those neighborhoods with buildings burning these environmentally corrosive oils.

Establish transparency of viewpoints

In the early phases of the collaboration, private interests including real estate and energy companies were worried that phasing out No. 4 and No. 6 heating oils would be too costly and harm their bottom lines. The NYC Clean Heat team, with the City of NY and EDF leading the effort, listened to these concerns and came up with financing solutions that would help buildings and other private sector participants shift to cleaner technology in ways that realize operating savings.

Share a vision of success

EDF and the City of New York acted as conveners, bringing the right people to the table to create the NYC Clean Heat Task Force and solve problems that inevitably arose along the way. They brought together stakeholders from real estate, finance, and community environmental groups to discuss the issues involved in phasing out No. 4 and No. 6 heating oils. Collaborators used these discussions to get an idea of what mattered to each sector and come up with solutions that worked for diverse participants. They created a City program that took into account aspects of the transition for all those involved, such as financing for buildings and assistance with the technical and engineering aspects. The switch to cleaner fuels was a positive not only for the city’s air quality, but also for its buildings and their owners. Cleaner fuels increase building efficiency and decrease maintenance costs; oil companies that produce cleaner oils stand to benefit from the transition through access to new markets; and the city phases out the dirtiest oils more rapidly. Perhaps most important of all, New York City residents got cleaner air quickly.

Demonstrate organizational competency and an ability to execute

NYC Clean Heat is a hub of resources, including technical and financial experts to ease the transition to clean fuels. The day-to-day functioning of the NYC Clean Heat program relies on participants from the City, EDF, and consultants hired by NYC Clean Heat. These technical experts deal with the buildings and owners, ensuring individualized help for each of the buildings. Consultants also advise buildings on selecting financing options, conversion options and energy efficiency.

Communicate the interdependency of each sector

City regulations requiring buildings to phase out the usage of No. 4 and No. 6 oils presented a challenge for some oil companies. The companies were concerned that all buildings would have to switch to natural gas, even though the infrastructure for natural gas was not available in all New York City neighborhoods, and some buildings prefer not to use it. NYC Clean Heat collaborators developed a menu of fuel options besides natural gas, including ultra-low sulfur No. 2 heating oil, biodiesel – and energy efficiency. This range of options allowed companies to participate in the transition toward energy-efficient and environmentally-safer heating fuels.

Share discretion

The NYC Clean Heat Task Force regularly updates stakeholders on program progress. It serves as a problem-solver: if a challenge best suited to a stakeholders’ expertise arose, that stakeholder could be quickly engaged. For example, while utility companies adjusted infrastructure, engineering and financing experts explained options available to facilitate buildings’ transitions, making conversions feasible through joint decision-making.

The NYC Clean Heat program is a model for large cities looking to transform buildings and the energy they use in ways that benefit health and climate. New York’s transition to cleaner heating fuels has been a win-win of lower operating costs and dramatic improvements in public health. The benefits the collaboration to public health are substantial: as of winter 2012-2013, sulfur levels had declined by 69 percent, nickel levels by 35 percent, and soot levels by 23 percent. According to a report by DOHMH, improvements in air quality are estimated to contribute to 780 fewer deaths, 1,600 fewer asthma-related emergency department visits, and 460 fewer hospitalizations for respiratory and cardiovascular disease each year. The report also estimates a 25 percent reduction in deaths attributable to soot pollution. Continuing achievements include:

- In 2008 to 2010, New York City was ranked number seven among the nation’s largest cities for clean air. In 2011 to 2012, the city was ranked number four.

- Approximately 3,500 of 10,000 initially identified buildings have already been converted to cleaner fuels, with an estimated 75 percent of these buildings now using either of the two cleanest fuels, natural gas or ultra-low sulfur No. 2 blended with biodiesel. An additional 1,500 buildings are now in the process of finishing their conversions.

- In 2012, there was a 16 percent drop in consumption of No. 6 heating oil, decreasing from 228 million gallons to 161 million gallons.