The Bethlehem Steel Plant closed in 1995, leaving an abandoned 1,800-acre industrial site comprising 25 percent of Bethlehem’s land. The country’s largest privately owned Brownfield – a site that had been used for industrial purposes that can be used once hazardous waste or pollution is cleared – redevelopment presented the City of Bethlehem with a challenging opportunity. The plant was located in Bethlehem’s SouthSide, a neighborhood with a median household income of $23,000, where 28 percent of the residents live below the poverty line and 63 percent are from minority groups. As part of the overall Bethlehem Steel Plant redevelopment project, the city worked with Bethlehem Steel and several investors to develop a plan to convert a 135-acre plot for both commercial and cultural use, a development site known as Bethlehem Works. When the first plan, anchored around an industrial museum, failed to generate strong interest, former director of Bethlehem city’s Community and Economic Development department Tony Hanna, along with Mayor John Callahan and others, proposed a partnership with casino conglomerate Las Vegas Sands, a local arts NGO, and the Department of Community and Economic Development to plan and design the site to feature a casino, conference center, hotel, outlet mall, and a new arts and cultural center. The casino and its environs generate new revenue and provide jobs, while the SteelStacks arts and cultural center offers modern, cultural programming together with community education and outreach initiatives.

Community and Economic Revitalization in Bethlehem

About This Project

“We have always believed that you can’t have successful economic development without an even more successful community development effort. Without strong neighborhoods and housing stock, commercial development will not only be difficult, but ultimately will fail and be unsustainable.”— Tony Hanna, Executive Director, The Redevelopment Authority of Bethlehem

Download this case study »

Tony’s career focused on real estate, community and economic development, and finance; his expertise served him well when serving as the Director of the Department of Community and Economic Development charged with assisting in the redevelopment of the former Bethlehem Steel site. Tony communicated with the community and the Las Vegas Sands Corporation to facilitate a sustainable and actionable plan that accounted for the interests of each group. Now serving as the Executive Director of Bethlehem’s Redevelopment Authority, Tony focuses on the continued development of the Bethlehem Works site.

Balanced Motivations

Tony is the first public official to receive the Frank L. Marcon Award, which recognizes individuals who have combined a distinguished business career with sustained and diverse community volunteer service that enhanced significantly the quality of life in the Lehigh Valley. Tony grew up in an economically distressed neighborhood in Allentown, Pennsylvania and believed in the importance of community within cities. Regardless of whether his job at the time was in business, non-profit, or government, Tony felt there were responsibilities attached to being successful and that success put him in a position to help others. Using resources at his disposal or influencing the use of community resources for the public good was a constant priority for Tony. He carried a belief in “communal interest” which influenced his orchestration of development projects, incorporating opinions of the citizens as well as developers.

Prepared Mind

Tony worked for ten years in Allentown government, specializing in finance, economic and community development, and planning and zoning. During this time, he helped found the Allentown Economic Development Corporation where he worked as the Executive Vice President; he likewise worked on initiatives designating National Historic Sites in the city. Tony never intended to stay in government for his entire career. Capitalizing on the strong economy of the early 1980s, Tony chose to transition to the private sector where he made real estate and healthcare investments and sold and arranged financing through municipal bonds at a small investment banking and development firm. He started his own consulting and development firms as well, feeling that ownership would allow him more control over the direction and growth of the business, as well as to better promote its agenda. However, Tony felt most fulfilled and rewarded while working in government; he returned to government first as a hospital administrator and then as the executive director of the Historic Bethlehem Partnership. As the Director of the Department of Community and Economic Development and the Redevelopment Authority, Tony has taken great pride in helping to reinvent and redevelop Bethlehem.

Contextual Intelligence

Tony’s career path allowed him to understand the motivations of each partner involved with the Bethlehem Steel redevelopment. His early career in economic and community development in Allentown’s government consisted of communicating with constituents about proposed development plans, which engendered a sense of empathy towards community interests. The community was most concerned with the preservation of the plant’s historic blast furnaces and other historic structures associated with steel making in Bethlehem, a concern Tony and others conveyed to the casino. His work as a real estate developer allowed him to ‘speak the same language’ as the Sands Casino developers when negotiating competing interests.

Transferable Skills

Tony’s extensive career afforded him the opportunity to work in different fields using a similar skill set. His experience in real estate, finance, and development within business and government enabled him to analyze large-scale real estate transactions and determine the likelihood for success. These skills includes project management, financial planning, and strategic planning. In working with communities, Tony acquired the relevant listening skills and ability to explain projects in relevant terms to each audience.

Recruit a powerful sponsor or champion

John Callahan used his position as the Mayor of Bethlehem to help connect stakeholders and to voice his support for gaming to community groups as a necessary step for generating development revenue; while the community’s initial response to creating a casino was roughly 50-50, when the issue was framed as helping to carry out historical preservation and community projects such as SteelStacks, approval rose to roughly two-thirds. The Mayor thus presented the casino as the driving force to fulfill the development vision that the town supported. As a supporter of arts and culture as an engine for economic development, Mayor Callahan positioned the collaborative development as a way to draw creative types to the community, which would advance the area’s continuing transformation.

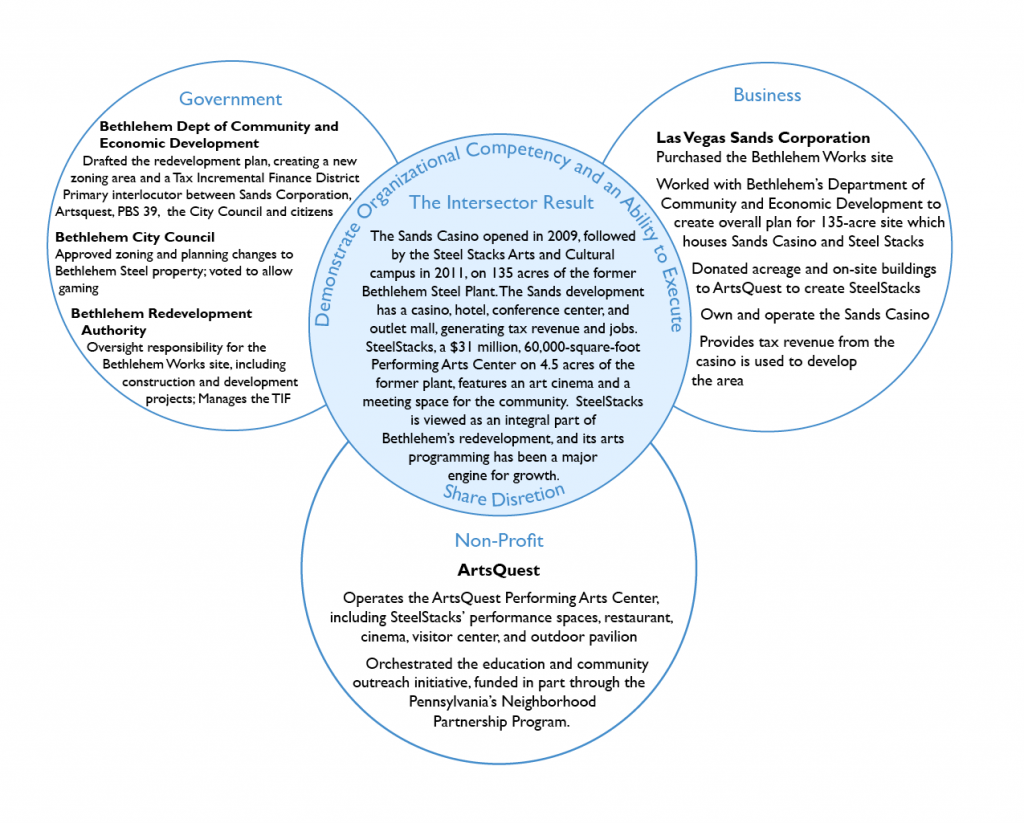

Demonstrate organizational competency and an ability to execute

Tony and the Development Department were instrumental in getting the city council to approve gaming, without which there would not have been a deal. Pennsylvania had recently legalized gambling, but the Mayor and Tony needed to show the community and City Council that the steel plant’s historic blast furnaces and other significant historic structures on the site could only be saved with revenue from gaming. The Development Department was also the driver, explaining to Sands Corporation that if they included historic preservation elements in their planning, they were more likely to receive support from the community. By coordinating with both sides, the city department was able to cultivate a plan that benefited all partners. City Council voted to approve gaming, and the Sands Casino donated acreage to ArtsQuest and PBS 39 for a new public media center in order to preserve the blast furnaces and historic factory and establish the arts and cultural campus, known as SteelStacks.

Communicate the interdependency of each sector

When the Bethlehem Steel Plant closed, there was consensus that the future economy of Bethlehem depended on economic diversification. Government participants relayed the interdependency to both sides: first, they informed Sands of the community’s interests in the deal, and that meeting these demands improved the casino’s chances. Likewise, they explained to citizens the benefit of income from a high revenue business such as a casino. ArtsQuest, which had approached the government about setting up an arts campus as part of the redevelopment plan, gave the community an opportunity to get on board with the plan. The City Council was integral in approving gaming, while the Department of Community and Economic Development assisted in outlining the overall scope of the initiative.

Share discretion

The city’s Economic and Community Development Department and Planning and Public Works, alongside executives from Bethlehem Steel Corporation, consultants, planners, and engineers, created a plan for redevelopment, sourcing funding from state and federal grants, as well as through a new Tax Incremental Financing (TIF) .The City was responsible for establishing the initial zoning changes to the site. The City partnered with Sands Casino and its for-profit partners BethWorks Now and BethWorks Retail to manage the planning process for the casino and associated retail and commercial space. By 2010, revenue from the TIF allowed the government to reestablish work with the Bethlehem Redevelopment Authority, who would be instrumental in revitalizing the old Bethlehem Steel site. The redevelopment plan also ensures continued support for SteelStacks and Bethlehem Works by future government bodies, and future owners of the Bethlehem Steel property.

Over 20,000 jobs were lost when Bethlehem Steel Plant closed in the 1990s, prompting serious concerns about the city of Bethlehem’s future. As part of an overall revitalization, SteelStacks and the Sands Casino have generated income, jobs, artistic programming and community programming in the South Side neighborhood, signaling a successful piece of Bethlehem’s revitalization plan. The collaborative planning process, coupled with a tax-fueled financial plan, resulted in the revitalization of 135 acres of the former Bethlehem Steel Plant, including its historic buildings. Within a larger development project, which also includes a roughly 1600-acre commerce center, the Bethlehem Works site offers new life to the steel plant combining arts and culture with commerce and entertainment. A 2012 report published on thirteen cities by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia noted that Bethlehem had the highest median household income, the lowest poverty rate, the lowest violent crime rate, and the second lowest unemployment rate.

- The Redevelopment Authority is now working on renovating the Hoover-Mason Trestle, a former industrial trestle, into an elevated walkway connecting the casino and the arts center.

- The ArtsQuest Center at SteelStacks has generated nearly $29 million in revenue since opening, and it’s Levitt Pavilion hosts 50 free community concerts per year.

- The SteelStacks Partnership for Education and Outreach, made possible in part with funding from Pennsylvania’s Neighborhood Partnership Program, has launched a ten-year initiative “aimed at providing arts, culture and education programs and opportunities that aid neighborhood stabilization and drive economic revitalization of distressed areas.”