Since the 1950s, the Rocky Flats Plant in Golden, Colorado, produced every plutonium trigger for U.S.-made nuclear warheads. But a 1989 raid by the FBI put a stop to the site’s nuclear production, its operators later pleading guilty to criminal violations of environmental law. Five years later, Rocky Flats sat unused and badly contaminated. The Department of Energy (DOE) called the site “one of the country’s most significant nuclear vulnerabilities,” projecting that cleanup would take 70 years and cost $36 billion. That same year, DOE awarded management of the cleanup to Kaiser-Hill Co., where Nancy Tuor served in a series of leadership roles before becoming CEO during completion of the contract. DOE, Kaiser-Hill Co., the Rocky Flats Coalition of Local Governments, and a non-profit Citizens Advisory Board, which included community, activist, and government representatives, worked together to ensure the cleanup effort met the needs of the community and federal regulations. In 2000, Kaiser-Hill and DOE agreed to a second, unique “closure” contract, which fast-tracked site cleanup to be complete by December 2006. Kaiser-Hill completed physical cleanup of Rocky Flats in October 2005, more than 50 years ahead of projections and 14 months ahead of the contracted target. Since 2007, the former nuclear weapons plant has been managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service as a National Wildlife Refuge, home to herds of mule deer and elk, along with the threatened Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse.

Turning a Former Nuclear Weapons Plant into a Wildlife Refuge

About This Project

“We, the collective we, all 6,000 people that were engaged, basically took something that was a significant potential risk to the Denver Metro area and a huge environmental liability, and… did something nobody in the world thought we would be able to do.” — Nancy Tuor, former CEO Kaiser-Hill Co.

Download this case study »

A longtime non-engineer leader within the engineering firm CH2M Hill, Nancy managed the company’s Southeastern US business before her former mentor tapped her to join the Rocky Flats contract bid team. Early in her career, she managed community outreach for the nation’s Superfund cleanups of uncontrolled hazardous waste sites, providing her with significant insight into the complexity of stakeholder viewpoints. Her commitment to proving naysayers wrong, combined with an understanding of the need for collaboration, made her an ideal candidate to oversee the complicated conversations and encourage the worker innovations that led to the cleanup at Rocky Flats.

Contextual Intelligence

Nancy established the community relations plan for the EPA’s Superfund program in the early-1980s, interviewing local community stakeholders about their views. She realized quickly that the national government didn’t understand or want to engage with local communities on these projects. This time spent as the EPA’s “sacrificial lamb” to Superfund communities exposed her to emotionally driven activist arguments. This led to her interest in Peter Sandman’s risk communication research, showing how the lack of ability to make decisions about an issue makes people less willing to accept risk. Together, this knowledge helped her engage with non-profits committed to preserving nuclear waste sites to serve as examples of this importance of disarmament and the government entities that needed to embrace collaboration with them. Her time running CH2M Hill’s business organization provided an understanding that the business community would resist job loss resulting from a plant closure. This broad understanding of motivations helped Nancy to frame negotiations from a standpoint all could relate to: a safe, thorough cleanup that would turn a community blight into a community asset.

Balanced Motivations

Nancy grew up with parents who taught her that community engagement was just part of how you live your life. Constantly volunteering with school activities, local Cub Scout troops, or public utility boards, her parents helped to ingrain within Nancy a natural desire to give back. Though Nancy turned down the position on the Rocky Flats team three times, eventually her mentor Bob Card won her over with the promise of getting to do something nobody else had ever tried to do – cleanup, in record time, a site that posed only potential danger for the community in which it remained. She realized the Rocky Flats clean up “was the project of a lifetime” in terms of its ability to contribute positively to the surrounding communities. She also felt driven by a need to prove wrong those who doubted her companies’ ability, and freely admits to being someone who hears “can’t” as a challenge to “figure out how I can.”

Transferable Skills

Early in her career, Nancy decided to get involved in local Oregon politics where she learned the art of “managing by influence” through her work on environmental and women’s issues. During this time, she served as president of the Oregon Women’s Political Caucus where she worked closely with several community groups and with the state legislature. This experience taught her to strategically “organize information to influence people,” steering them to follow the course that her organization desired. These skills became a core part of how Nancy conducted business throughout her career, eventually helping her influence outcomes on controversial issues that arose during the Rocky Flats project.

Prepared Mind

Nancy built her career on seizing opportunity when it presented itself. With her early political volunteer work and several years working in the environmental field for government clients such as the EPA, Nancy recognized an exceptional government sector role when it came along. She met with the head of a new Department of Land Conservation and Development, thinking it was a marketing opportunity for her company. Impressed with the agency’s director, she decided instead to take “a great job at a great time”as program division manager, where she spent two years overseeing the agency’s coastal zone management program, along with legal staff, legislative affairs, and government agency coordination. But Nancy always expected her foray into government would be temporary, and that the private sector would pull her back with its project-focused work, challenging but distinct goals, and intelligent, driven leaders. When CH2M Hill came calling 2.5 years later, Nancy made the shift back to the private sector.

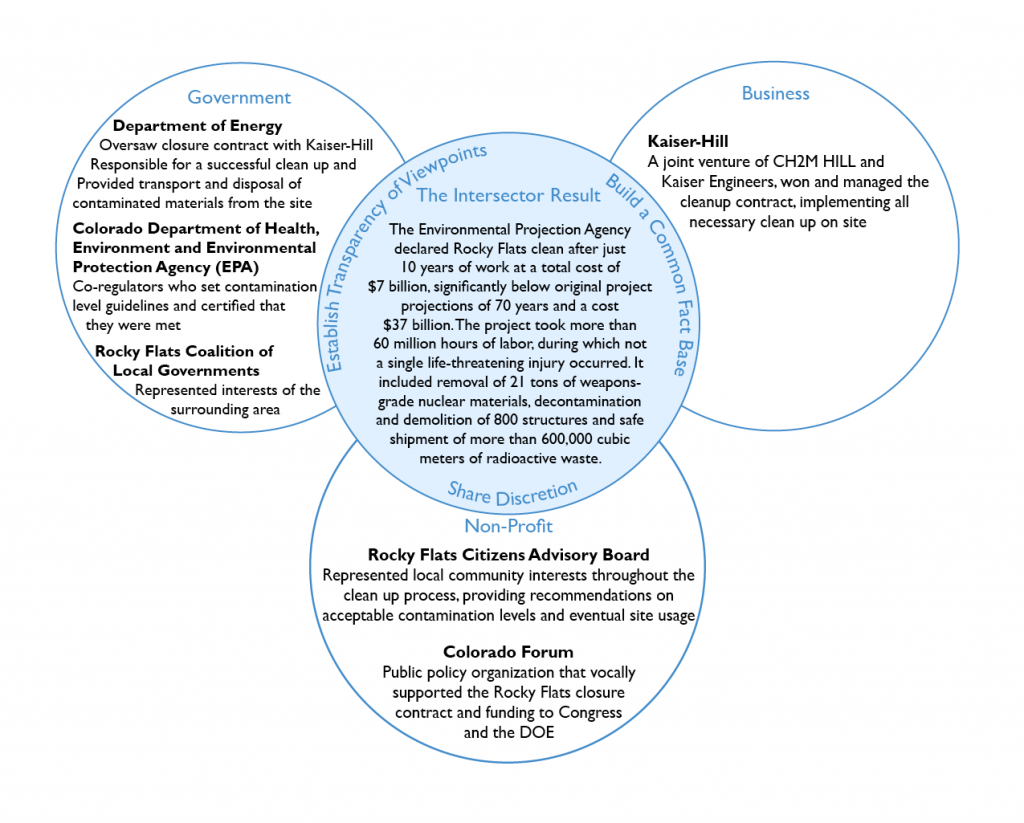

Establish transparency of viewpoints

The clean up process for the Rocky Flats site required regular meetings with cross-sector partners to discuss differences of opinion and present recommendations for next steps. Governmental regulators, DOE, Kaiser-Hill and community groups all participated in conversations about what levels of contamination could be left at Rocky Flats. Though many environmental groups preferred to leave Rocky Flats to serve as a warning sign against future nuclear development, large group stakeholder meetings provided a forum that allowed for community interests to be part of the conversation. While decision-making authority for acceptable contamination levels rested with the EPA, these forums often pushed the regulator to revise their proposal to take other interests into consideration.

Build a common fact base

Among the many opportunities for disagreement among partners, the acceptable level of remaining soil contamination was a contentious issue. Since plutonium binds to soil, surrounding communities were very concerned about what remaining contamination would mean for future use of the land. DOE provided funding to concerned citizens’ groups so they could hire consultants to conduct their own research. Kaiser-Hill also conducted modeling assessments, as detailed as “how prairie dogs burrowing moved the soil.” Each organization shared their findings with one another, as well as committed to a two-year negotiation process to come to agreement on what contamination levels were tolerable at various underground depths. Nancy worked with her communications team to ensure that the information Kaiser-Hill provided was not only accurate and relevant to the discussion, but also presented in a format that made the highly technical information simple to understand to allow for informed decisions.

Share discretion

Nancy and the Kaiser-Hill leadership team led the creation of a unique formal “closure” contract, which included penalties and incentives tied to the company’s ability to meet specific performance metrics. Under this agreement, DOE set the goals for the contract, and Kaiser-Hill determined “the how” of getting things done. DOE also created and funded a non-profit Citizen’s Advisory Board, with community, activist and government representatives. This board developed and forwarded 177 recommendations to DOE and regulatory agencies on the Rocky Flats clean up throughout the process, which they were able to share in semi-weekly meetings of the Rocky Flats Clean Up Agreements Focus Groups, attended by representatives from Kaiser-Hill, DOE, and the Rocky Flats Coalition of Local Governments. This arrangement ensured that all partners’ voices would be heard, and that each group could focus its efforts on their respective areas of expertise.

Recruit a powerful sponsor or champion

Nancy recognized that the divisive issue of cleaning up nuclear site and a unique funding and contract structure would require supporters in high places. The Kaiser-Hill leadership team deliberately hired two well-respected environmental leaders – Dave Shelton, who previously led Colorado’s hazardous waste program, and Melinda Kassen, former attorney for the Environmental Defense Fund – to help them develop a strategy that would engage all stakeholders. She then identified the need to engage local governments as a way to amplify voices of citizens who were interested in a safe, community-friendly cleanup, so Kaiser-Hill recruited Lt. Gov. Gayle Schoettler, who worked with local government leaders to convene the Rocky Flats Coalition of Local Governments. This organization became instrumental in developing a scope of work that meet the safety needs of surrounding communities. Nancy also engaged Colorado Forum Director Gail Klapper, who recruited Senator Wayne Allard to set Rocky Flats closure as a top priority. He protected contract funding and pushed the Rocky Flats agenda with DOE throughout the process.

Despite original DOE projections that it would take 70 years and $36 billion to successfully clean up the Rocky Flats nuclear production facility, Kaiser-Hill completed cleanup in October 2005, in just 10 years and at a cost of $7.4 billion. The company even beat the goals outlined in the accelerated target closure contract – 14 months ahead of schedule and $500 million under budget. Former Colorado Sen. Wayne Allard called the project “the best example of a nuclear cleanup success story ever.” The collaboration was created by a unique, forward-thinking DOE contract that put Kaiser-Hill on the line to deliver extraordinary results quickly, safely and cheaply. During the project, Kaiser-Hill removed more than 21 tons of special nuclear materials, cleaned up and demolished more than 800 facilities, and disposed of more than 600,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste. They also distributed $100 million dollars in incentive pay to site employees over the 10-year contract period.

- Today Rocky Flats is managed as a National Wildlife Refuge of more than six square miles of open between Denver and Boulder. The site is home to a mix of native grasses and various animals, including deer, rattlesnakes, hawks and the threatened Preble’s meadow jumping mouse.

- The cleanup collaboration has been featured in Triple Crown Leadership, a book that outlines outstanding business practices, and Making the Impossible Possible, a book that serves as a case study on exemplary leadership for University of Michigan business students.