Colton Crossing, in Southern California’s San Bernardino County, is one of the busiest railway junctions in the US, serving as many as 120 trains per day. In addition to the Crossing’s two intersecting tracks, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway (BNSF) north/south track and the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) east/west track, the Metrolink and Amtrak commuter lines all use the junction, requiring trains to idle at the crossing for over 50 minutes on average and up to four hours. Railway traffic was projected to double by 2020. A grade separation – a bridge that disjoins overlapping rail lines – would allow for more commuter and cargo trains to pass through Colton at faster speeds, and would reduce air pollution caused by idling trains. Individually, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), the City of Colton, private railways, and commuter lines were unable to shoulder the cost of constructing a grade separation, and their divergent interests prevented them from working together. Garry Cohoe, Director of Project Delivery for the San Bernardino Associated Governments (SANBAG), was called on to develop a plan and to guide a collaborative effort between the multiple stakeholders. Garry was able not only to bring together the various stakeholders, but also get the residents of Colton behind the plan, dividing the costs of construction and responding to the concerns of all involved.

Constructing a Grade Separation for Colton Crossing

About This Project

“The Colton Crossing Project’s success reflects a great opportunity to revolutionize the methods in which large-scale collaborative efforts are managed not only in the Inland Empire but also throughout the nation.”– Colton Crossing: A Model for Public-Private Partnerships A. Busch, et al., Editors. 2013, Inland Empire Outlook: Claremont, California

Download this case study »

Garry, Director of Project Delivery for San Bernardino Associated Governments, understood that in order to successfully build a grade separation for Colton Crossing, he would need to get the government, railways, and residents to reach consensus. His department is responsible for major highway improvement projects, and he had also worked as a city engineer, as an office manager at a private firm, and as a supervisor for Caltrans before becoming a director at SANBAG. His extensive experience in the transportation field and in management positions in both the public and the private sectors made him ideal to lead this collaboration.

Transferable Skills

With over twenty years of management experience, Garry knew how to facilitate open communication between parties and listen to all sides of an issue. He put those skills to use early in his career and developed a reputation for successfully managing large construction projects. In 1991, when Garry worked for Caltrans, former Chino Hills Mayor Gwen Norton-Perry recruited him to be the city’s first City Engineer. Garry was involved in the management of a new multi-building government center, the largest project the City had undertaken. Garry’s ability to understand the interests of multiple stakeholders and to find solutions to satisfy all parties led him to join SANBAG, where he managed even larger projects.

Integrated Networks

Garry occupied several leadership roles in both city government and transportation; in the private sector as Office Manager for Carter & Burgess Engineering and in the government sector as City Engineer for Chino Hills. His government experience also included three state level positions with Caltrans: supervisor of a design team, District Deputy Director of Design, and District Deputy Director of Program/Project Management. At Caltrans, he often served as the public face of projects,, and had a positive reputation with community leaders that added to his credibility. Garry’s experience across sectors enabled him to bring leaders from government, business, and the community together to complete projects.

Contextual Intelligence

Garry was a well-qualified leader for the Colton Crossing project, bringing years of professional experience in the transportation field on both the public and the private sides as well as extensive practice appealing to local communities. He was able to capitalize on his understanding of each sector’s concerns, including those of Colton residents, to facilitate an agreement between sectors.

Intellectual Thread

With more than twenty-two years of experience in the transportation field, Garry possessed expertise in transportation engineering and financing. For sixteen years, he has served as a manager in the transportation industry – six of which as a Director for SANBAG. His vast experience and his knowledge about leading major transportation projects were put to use with the Colton Crossing Project.

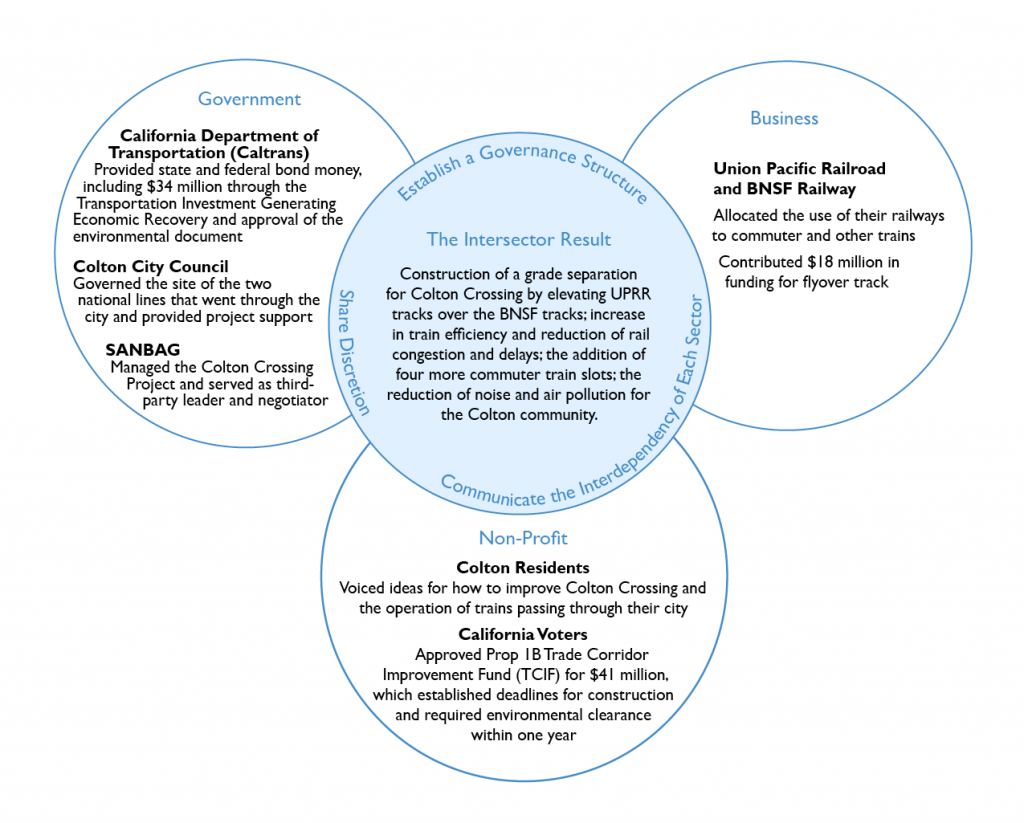

Establish a governances structure

Since Caltrans controlled state and federal funding, the private railways did not view it as a disinterested party. The railways chose SANBAG as a trustworthy third party manager to control the project, and Caltrans agreed to allow them to lead. SANBAG has developed a reputation for being a reliable, neutral party to broker agreements among stakeholders; In 2010, for example, SANBAG completed a grade separation for Ramona Avenue in Montclair. That project required them to mediate between the City of Montclair and UPRR, and to manage both state and federal funds. SANBAG began its work on the Colton Crossing Project by holding public meetings to facilitate conversation between BNSF, UPRR, other railroads, the City, and Caltrans.

Communicate the interdependency of each sector

Funding disagreements had stalled negotiations for improving Colton Crossing for decades. However, in 2008, California voters approved the Prop 1B Trade Corridor Improvement Fund (TCIF), providing $41 million in state funding for the Colton Crossing Project. The funding agreement stipulated that the project be far enough along to pass environmental impact standards within one year. The passage of Prop 1B coincided with the federal government’s awarding of $34 million in stimulus package grant money to California through the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery Act. Caltrans controlled the state and federal funding and wanted local residents to support whatever project the City of Colton and the railways formed. All stakeholders understood the rarity of this funding opportunity but they still needed to come to an agreement and to win public support within a year for the Colton Crossing Project to be realized.

Recruit a powerful sponsor or champion

SANBAG’s management of the Colton Crossing Project took the form of face-to-face meetings with stakeholders, including members of the City of Colton’s city council. Garry included Colton’s City Manager, Rod Foster, in negotiations concerning the Colton Crossing project. By including a representative for the residents of Colton in the negotiations, Garry garnered public support for the project.

Share discretion

The City of Colton wanted a depressed line built underground for BNSF to pass under UPRR, a plan that would have cost over $1 billion. The financial contribution required by the private railways was too great, and the parties were at a stalemate. SANBAG conducted massive public outreach, held town hall meetings throughout Colton and the surrounding area, and put pressure on the government and business stakeholders. One community group in particular voiced disagreement with the City’s plan to dig a trench and construct a depressed line. During the meeting, residents came to the consensus that elevating UPRR’s line over BNSF made the most sense. Council members in attendance relayed the community’s position to other members of City Council. Shortly after that town hall meeting, the Mayor of Colton spoke in favor of an elevated line instead of a depressed line, and the City of Colton finally reversed their position. Caltrans then awarded grant monies to the Colton Crossing Project, with BNSF and UPRR providing the remainder of the funds. Construction began in November 2011 with construction to last three years.

Demonstrate organizational competency and an ability to execute

Colton residents were concerned about train sounding their horns at street crossing and the impact trains had on vehicle traffic. SSANBAG, BNSF, and UPRR agreed to fund “Quiet Zone” improvements, so that trains would not need to sound their horns at street crossings. In addition, they constructed a new grade separation at an arterial street and removed a railroad spur line from the middle of a residential street. This fostered residents’ good will towards both government bodies and private railroads early in the construction process.

Share a vision of success

All sectors understood what completing the Colton Crossing project would mean for the city, businesses, and the local community – reduced railway congestion, reduced noise and air pollution, and fewer delayed trains. Their mutual understanding of the benefits of success and the consequences of failure led stakeholders to cooperate in unique ways. UPRR even financed improvements on the BNSF line to make sure the project was a success. Their contribution to the BNSF track improvement allowed the construction to move forward as scheduled.

Construction of the flyover grade separation for Colton Crossing was completed in August 2013, eight months ahead of schedule and over $100 million under budget. The Colton Crossing project created around 2,000 jobs, significantly contributing to the regional economy. The decrease in train congestion also permitted four additional commuter lines to travel in either direction, which likewise benefited the City of Colton residents. Since trains no longer had to wait at the intersection, the transportation of goods ran more efficiently as well. The value of the public benefits of the Colton Crossing Project in terms of efficient transport of goods, commuter rail services, and job stimulus was over $125 million, which exceeds the public contribution in tax dollars.

- According to Caltrans Director Malcolm Dougherty, the construction of the flyover will save $241 million in travel time and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 34,000 tons each year.